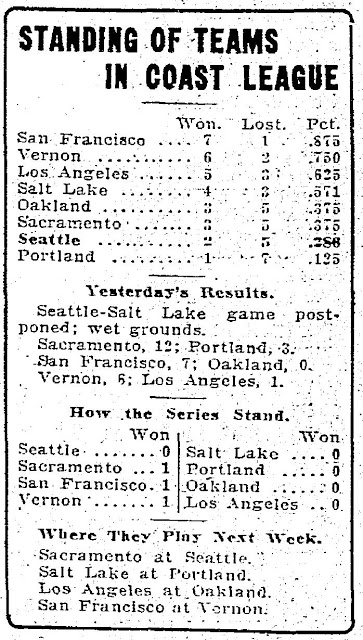

The first week of the season, the Seattle Indians' bats were just awful enough for last place. For whatever reason, reasons probably having more to do with the Angels pitchers starting strong than anything else, it took a train ride to the still-in-winter confines of Bonneville Park in Salt Lake City before Seattle started finding the ball with any consistency. Wade Killefer stated during spring training he thought the Indians would have a good hitting team that year. That is what started to emerge during the second week of the season.

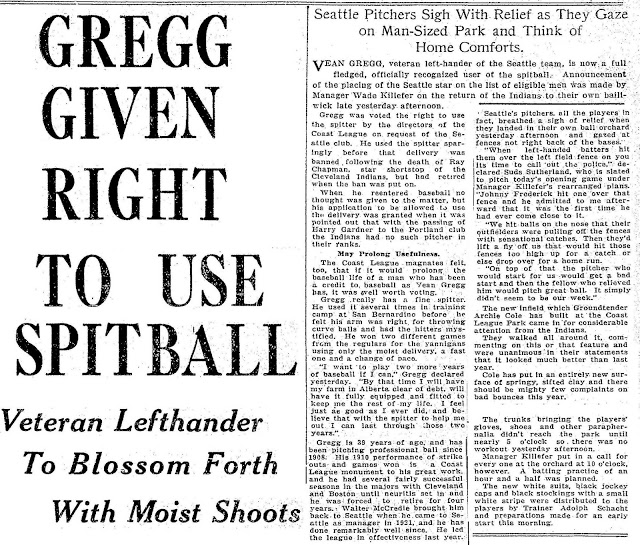

Spring training began for pitchers and catchers in the hot springs at Elsinore on March 2, 1924, followed by all players reporting on March 9 in lovely San Bernardino where they headquartered at the classic Stewart Hotel. The team left Riverside County just before the start of the season to stay in Los Angeles and complete spring training.

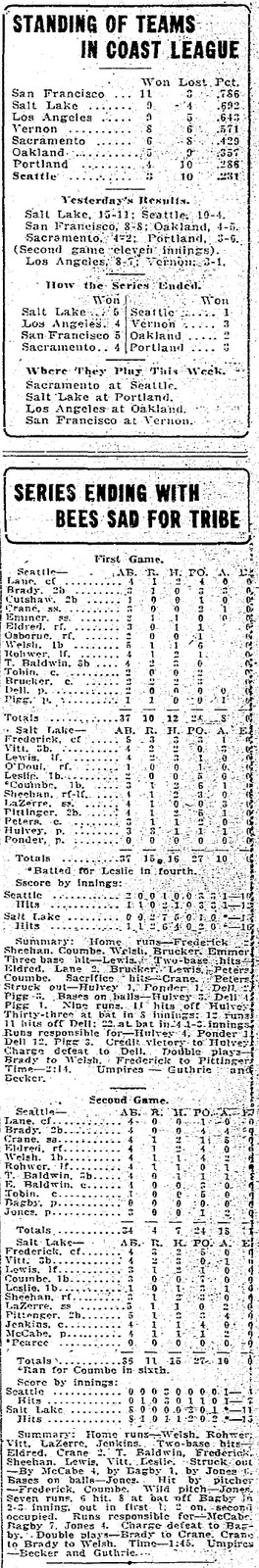

The results of the first two weeks was a 3 and 10 record at the hands of good pitching in LA and good hitting in SLC.

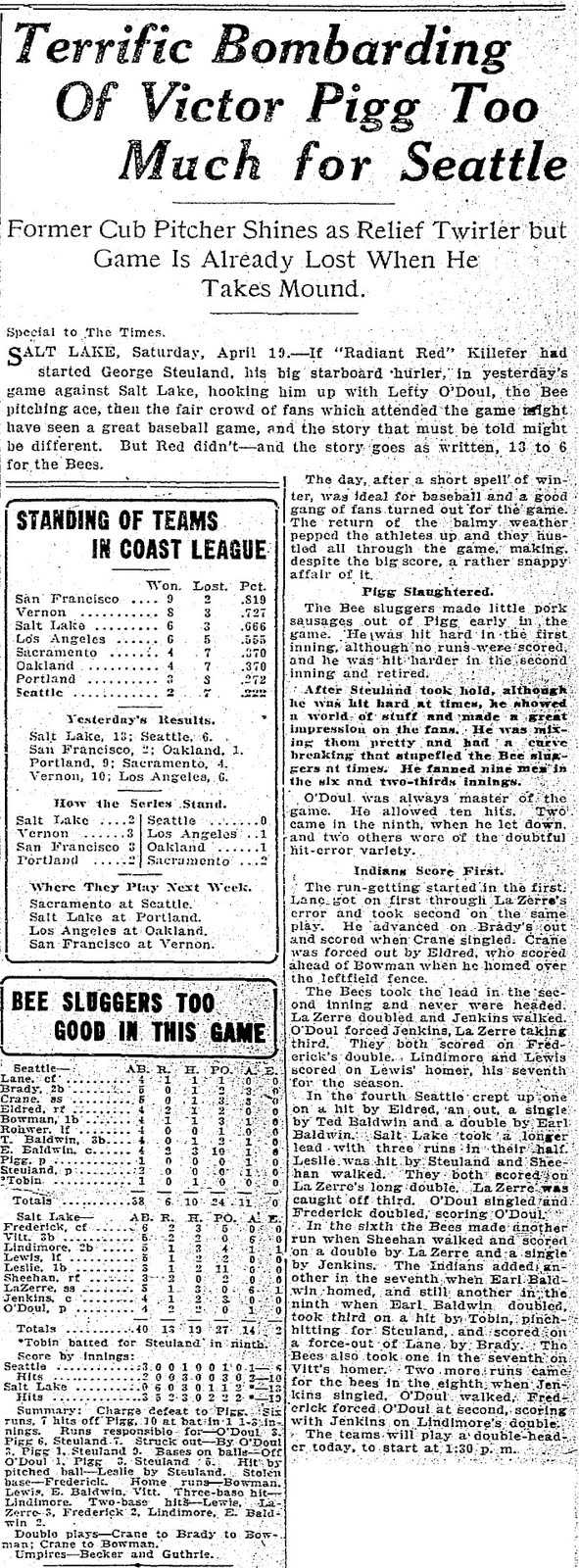

The Salt Lake Bees were a club that would feature the two best hitters in the Pacific Coast League that year, Duffy Lewis and Lefty O’Doul, anchoring a lineup that would lead the PCL in batting at .327, and that power proved to be the dominant factor in that series. But, against Sacramento, Seattle started to finally put it all together.

The Seattle bats were finally waking up for good on the train ride home to Seattle’s Coast League Park, as Dugdale Field was referred to in many of the news reports of the 1924 season. When the players had converged in San Bernardino for Spring Training, they left off-season homes in such places as Texas, Missouri, and the Bay Area. After a little over a month, they had moved spring training to Los Angeles before starting the season against the Angels. Then, finally, after a week in Salt Lake in late April, they were in what for many was a home away from home, the Rainier Valley of Seattle.

Ray Rohwer continued to be an on-base machine, now having reached first base in 13 consecutive trips to the plate. He hit a home run, a triple, and put across 2 RBI’s in this game, a remarkable display of power for a hitter who had walked in 4 straight trips to the plate the previous day. Ray Rohwer had gone straight to the Pittsburgh Pirates from the University of California, although his playing time had been interrupted by service in World War 1. I’m not sure how, still need to investigate, he was allowed to play for California in the 1920 season in spite of the fact he graduated in 1917. Rohwer hooked up with Pittsburgh in 1921 as a 26-year old rookieRohwer had gone to spring training in Texas for the Pittsburgh Pirates with his brother Claude, after both finished playing for the University of California. Ray was able to stick with Pirates for 1922 after showing some promise in spotty appearances in 1922. The after-the-fact highlight for Rohwer, and baseball history, was his go-ahead RBI single in the first ever baseball game broadcast on radio, on August 5, 1921. Rohwer came in to hit for first baseman Charlie Grimm, and lined a single, and also added a run to seal the deal. Unfortunately, he added an error in right field in the top of the ninth, but the Pirates still won 8-5 over the Phillies. The first game was actually a re-broadcast of sorts. It was on KDKA, the pioneering radio station in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The game was called by KDKA’s regular announcer, Harold Arlin.

Ray Rohwer could always hit, unfortunately for him, he was trying to break into the best hitting club in the National League in 1922 (the regular top four outfielders for Pittsburgh collectively batted .342 that year, with Max Carey’s .329 being the worst!). Left-handed hitting Rohwer was mostly used as a late-inning pinch hitter against right handed pitchers, but did get 28 starts among his 53 games that year. Although he finished 1922 with a .295 batting average (one of 11 Pittsburgh position players to hit at least .290), on July 1, following a double header, Ray was hitting .386 with a .446 on-base percentage and a .627 slugging percentage for an overall OPS of 1.072. Over a four game stretch he went 12 for 19. However, a slump followed, and on July 21, Rohwer lost any shot of getting the right field spot when left-handed hitting Reb Russell showed up from the Minneapolis Millers, completing a remarkable return to the majors for the former White Sox pitcher who had injured his arm in 1919. Russell came back from that injury as a power hitting outfielder, joining Carson Bigbee and Hall of Famer Max Carey in creating a formidable outfield for Pittsburgh. Clyde Barnhart also filled out the fourth outfielder spot, making Rohwer more valuable as a trading commodity than a fifth outfielder, especially since he was probably a 27-year old, what you see is what you get who wanted to get back out west. Rohwer was traded to Seattle on December 6, 1922, along with the first pitcher in Seattle to be called “Sherriff”, John Fred Blake, cash and a player to be named later for infielder Spencer Adams. Adams was considered a prized prospect, but would spend most of his career going from one team to the next, not spending consecutive years in any location until he was 31, at Nashville in the Southern Association. Rohwer was considered a good hitter, but the Seattle Daily Times article on the trade wondered if his fielding would be good enough to make it in the PCL.

Claude had been invited to Spring Training to possibly be the Pirates answer for third base. But in spring training 1922 they decided to give that shot to a young prospect they had paid $10,000 for, although he had projected to be a second baseman or shortstop. The young prospect, Pie Traynor, could hit, but his defense was suspect, and they still had Rabbit Maranville, a great and mercurial personality, if not shortstop, already. So, on the opening day of the 1922 season, Ray Rohwer found himself starting the bottom half of a double header against Cincinnati, only to be pulled before getting an at-bat, Claude Rohwer was playing shortstop for the Charleston Pals of the South Atlantic League, and at third base for Pittsburgh was the young prospect Claude lost out to, Pie Traynor. Traynor would go on to have a Hall of Fame career and generally be viewed as the National League’s premier third baseman between the Deadball era and World War II. Claude had a short career in the PCL, playing third base for Sacramento along with Ed Hemingway. My blind hope/curiosity suggests that Hemingway might be a second cousin or so of the other E. Hemingway. They are about the same age. I think at this time, Spring of 1924, Ernest is probably off in Paris or Pamplona preparing to be important. Claude would return, like the other Rohwer brother, to Dixon.

Meanwhile back in Seattle on a Saturday afternoon, across the board the hot hitting continued, and in an excellent sense of foreshadowing, the Indians pulled it out in the late innings. The pitcher on this day for the Senators was, like Rohwer, a former member of the Pittsburgh Pirates named Moses Yellowhorse.

It’s a curious thing to think about: why do some of us love a game so much? We dedicate hours, days, lives to the minutia and incidentals of some far away or at best parallel universe. Often times, as sports fans of an intellectual bent, we cannot even display great insight to our own form of play, this interaction with distance. Certainly some of this has to due with the element of play in the human psyche. Boyish, or girlish, or just adolescent, acts of self-definition. Some theories of art look at the impact of peak shift experiences on the individual exploring the plastic work. That is, what is it about a static object that incites engaged participation? I think that type of approach explains, also, the ‘art’ of baseball, or any sport. Many players, observers, reporters and critics have noted the theater of sport. Going back to the Roman Circus or Greek Olympics, sport was often lumped in with the various cultural activities of a celebratory nature. This was also true across America. We can attribute that somewhat to the post-Renaissance influence of classical societies, but I think this is more an accurate description of human tendency, rather than a fixed operation of particular origin. In short, the harvest festivals had sporting contests at their center, or at least near the center. In most circumstances it was a safer version of the hunt, or a more public exhibition of thrashing. And there was baseball. Baseball, as it grew into its oversized jacket as the American Pastime and then into the pastoral landscape of fogged collective memory, was nearly always a part of the community and its rejoinders of atonement, a process which in the industrial and advertised landscape that was always becoming, the Twentieth Century, became the moments in the days just past the harvest, where we find and fix the happenstance participants of a given time to a given space, that is to say we create myth’s from the substance as much as the essence of reality. Much like we remember where we last hunted a deer or the angle of the sun when the berries ripened, it is the forthcoming winter absence that seeks to gather collectively before we sink into the winter hive, and this festival, this gathering, is where we remember the significant moment of play, the winning comeback in the bottom of the eighth. Thus, an essential component of our fanaticism is the way in which it allows us to passively experience our hunter/gatherer past through both a satisfaction of the curiosity impulse implicit in the hunt, and the peak shift experience essential to the kill.

Another element essential to the development of fanaticism, one that runs parallel and is part and parcel of the fan, is the dual role in which re-imagination plays along with the experience factor: the apprehension of identity, or identifying with the players. The key there is what part of our identity the players, managers, or game itself, the game experience, with which we identify. Which brings us to Moses Yellowhorse and Ed Delahanty, two players connected for the purposes of this argument solely through the manner in which I identified with them at a certain age of my own life. Ed Delahanty was the first baseball player whose story I found inexorably fascinating. I was in middle school, in Olympia, and had run across his story in a book about the 50 greatest players of all time. For some reason, the irascible drunk who disappears after getting thrown off a train and trying to cross a trestle at Buffalo at night spoke to me. There was something in that irrational act, that lack of ending, with which I connected. The same with Yellowhorse. Much like the author of the book The (Baseball) Life of Moses Yellowhorse, Todd Fuller, I simply saw the name Yellowhorse and immediately recognized someone as probably being a fellow American with Native heritage. But, the story is much richer than that, because this is 1922, and Moses Yellowhorse was the first full-blooded Native American to play Major League Baseball. In 1922, its not really heritage as I see it, its life as a Pawnee, being lived. The world was not historical, but rather one of sharing experiences with those who are not part of the pastoral past, a world that ran fully against that notion and had to be brought into it through conflict; a world not populated with characters, but people with wounds, pride, and a child who could probably hunt by simply hurling a rock at a bird. He grew up on, and would return to, the Pawnee reservation, and went to school, and played baseball for, the Chilocco Indian Agricultural School. Yellowhorse came under the wing of former Yankee (Highlander) interim manager/player Kid Elberfeld, who by 1920 was in his mid-40s and managing the Little Rock Travelers of the Southern Association. Moses’ blazing fastball would get him to Pittsburgh in 1921, and he’d pitch 126 innings before an injury and alcohol would relegate him to the minors. His drinking partner was his roommate, the previously mentioned Rabbit Maranville. Moses would eventually kick the booze in 1945 and become a leader in his community.

In this 1924 game, Yellowhorse’s career is coming near its end as far as professional ball would go. He would only appear in 10 games that year, then two more in 1926 for Omaha. I highly recommend Todd Fuller’s book on Moses Yellowhorse. It uses poetry, prose, personal narrative, history and biography to tell this unique man’s unique story.

8,000 Seattle Fans See Tribe Rally And Beat Solons, 7 to 6

Going Into Eighth Inning Four Runs Behind, Local Team Chases Yellowhorse From Game With Fierce Attack.

REFUSING to be beaten even though the Sacramento team had them 6 to 2 when they went to bat in the eighth inning, the Seattle team staged a great rally in its half, drove in five runs with six terrific hits, a hit batsman and a base on balls, defeated Sacramento 7 to 6 and won its fourth straight home victory over the Solons.

A crowd estimated at 8,000, one of the largest Saturday crowds in the history of Seattle baseball, saw the thrilling rally.

Ted Baldwin’s home run over the right garden wall with Ray Rohwer on first base put the finishing touch to Mose Yellowhorse, chased him from the game with a tie score. Whereupon Lefty Vince came on, hit Tobin, walked Carl Williams and was hit for the winning single by Billy Lane.

Ray Rohwer, Seattle left fielder, contributed a triple, a home run and a single in his last three times at bat, and was given a base on balls in his first trip to the plate.

He has now stepped to the plate thirteen consecutive times and reached first base on every attempt.

Four hits, two of them triples, and a base on balls Thursday-

Four consecutive bases on balls Friday-

A base on balls and three consecutive hits Saturday-

That is Rohwer’s record.

Figured Game Lost

The 8,000 fans on hand figured the game gone when the Solons landed on Wheezer Dell in the sixth and seventh for five runs, which, with the one they had scored in the fourth, game them a five-run lead.

But Ray Rohwer boosted one over the fence to start the seventh. He had already scored a run in the fith when he hit the center field fence for three bases and rolled in on Ted Baldwin’s double.

Yellowhorse got them out in the seventh without further damage, but the eighth was-oh, so different.

Cliff Brady started the fight by singling to left.

Sammy Crane, who had already hit safely twice, doubled to left center.

Brick Eldred singled sharply to right, Brady scoring.

Elmer Bowman hit one hard right at Hemingway, however, and was doubled up with Eldred.

Two out, three runs to go to tie. It didn’t look exactly encouraging.

Ray Rohwer came up to try and do something for his thirteenth straight trip to first. He singled to right and Crane came over.

Ted Baldwin got hold of a fast one on the outside corner and over the right field fence it went. The score was tied.

Mose Yellowhorse left the pitching mound in bad order and Lefty Vinci came in.

Lefty hit Tobin in the leg. Then he walked Carl Williams.

Sensing that break Wade Killefer sent speedy Jimmy Welsh in to run for Tobin.

Billy Lane, with three and two on him, and the runners under way, singled across second, scoring Welsh and putting Williams on third.

Vinci also departed and Lefty Canfield retired the side with the Indians one run to the good.

Carl Williams blanked the Solons in their half of the ninth and the fourth straight was on the winning side of the ledger.

One Hit, All Hit.

It was the same story yesterday as it has been all week.

When one Indian hits they’re e all liable to start right after him.

Yesterday they wasted four hits, more than they had wasted all week, but it took some great playing to stop them as long as Yellowhorse did.

For instance, the Tribe was off on one of its rallies in the fifth. Rohwer opened with that long triple and scored when Ted Baldwin doubled over McNeeley’s head. Frank Tobin, who had received a big bunch of carnations from the Seattle local of the plumbers union, “Big Tob” being a member of the Sacramento local, hit one squarely on the nose to right field. Siglin made a marvelous stop and throw to first to nail him. Billy Lane followed with an equally hard-hit ball to left field that Merlin Kopp made a great catch on. Hemingway and Mollwitz had turned in some fine plays before that, too.

Dell Starts Well.

Wheezer Dell started as though he would need only one run to win.

For three innings he mowed the Solons down without a hit. Frank Tobin helped him out of his few difficulties with some great throwing. He stopped Hemingway stealing in the first and nipped McNeeley off of first in the third with a snap throw.

Kopp’s double, a sacrifice and Schang’s single broke the ice and put the Solons ahead in the fourth, the first time all week that they had been in the lead.

Dell had two out in the sixth before trouble overtook him. Hemingway singled and Siglin and Schange doubled for a pair of Solon tallies.

Three more came over in the seventh inning and caused Dell’s retirement in favor of Greg.

Crane booted a slow hopper from Mollwitz’s bat, and then was caught out of position on a hit-and-run play when McNeeley pushed a lazy single through short. Cooey McGinnis tripled to the left-field fence, scoring the pair and counted himself on Yellowhorse’s long fly to Lane.

Gregg came on, put out the side and retired in favor of “Papa” Frank Osborne, who tried to celebrate the arrival of a nine pound boy in his St. Joseph, Mo., home by pinch-hitting. McNeeley made a fine catch of his long line drive.

Then came Carl Williams, with the score tied, and the Solons were stopped dead and Texas Carl gets the credit for the win.

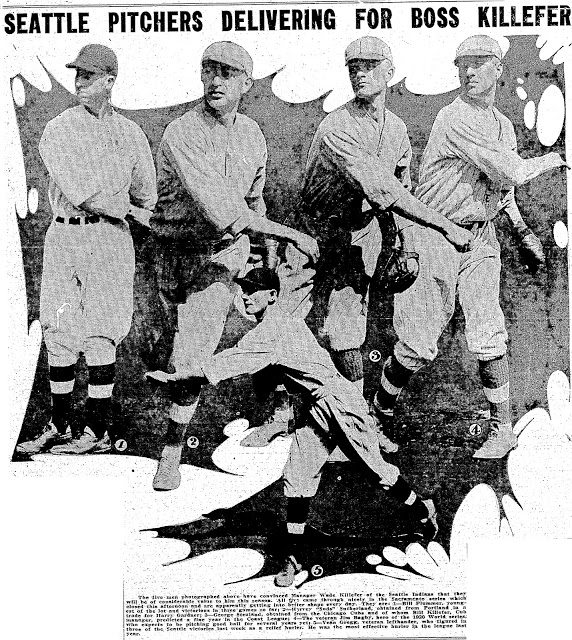

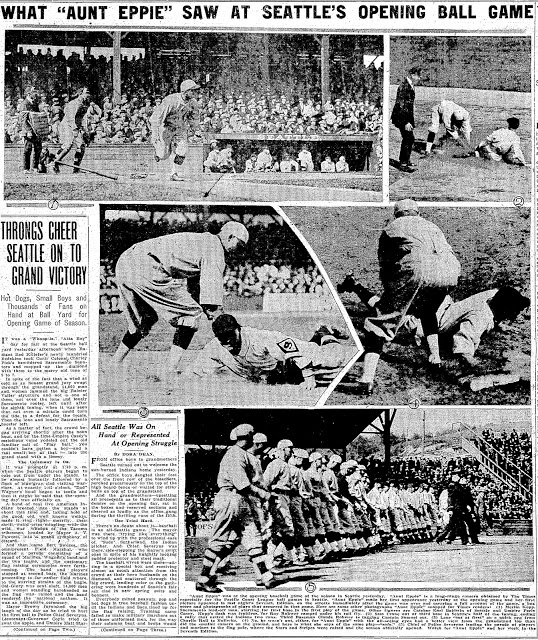

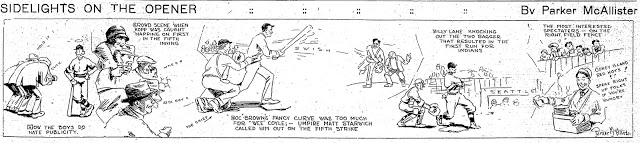

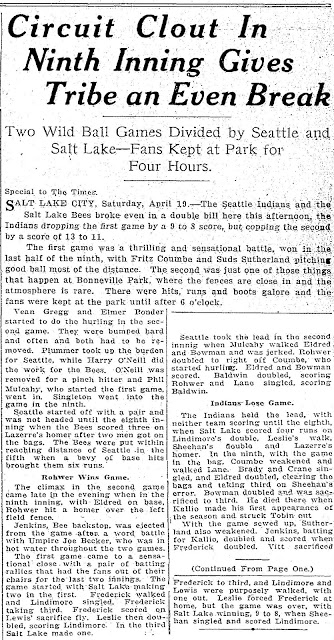

The photograph above is from a Tuesday, April 29, 1924 edition of the Seattle Daily Times. I’m not sure which edition, probably an early one since it details the previous day’s games. They had a new ‘long-range’ camera that year they had nicknamed Aunt Eppie. I’m pretty sure that has to do with the size of the camera. Aunt Eppie was also a recurring character in the Toonerville strips which appeared on the sports pages of the time. Could also be from some other cultural source, but I am not well read enough to know that..yet. The photo above is from the Monday, April 28, game between the Seattle Indians and visiting Sacramento Senators. This game was the final one is their 7 game weeklong series. In the PCL of the time, teams played each other each week for a weeklong series, and often used Monday as the travel day between series. In this instance, the game was played on the Monday since Sacramento only had to travel to Portland for its next series. The Indians’ next opponent was the Salt Lake City Bees, who would be coming up from Portland.

The photograph above is from a Tuesday, April 29, 1924 edition of the Seattle Daily Times. I’m not sure which edition, probably an early one since it details the previous day’s games. They had a new ‘long-range’ camera that year they had nicknamed Aunt Eppie. I’m pretty sure that has to do with the size of the camera. Aunt Eppie was also a recurring character in the Toonerville strips which appeared on the sports pages of the time. Could also be from some other cultural source, but I am not well read enough to know that..yet. The photo above is from the Monday, April 28, game between the Seattle Indians and visiting Sacramento Senators. This game was the final one is their 7 game weeklong series. In the PCL of the time, teams played each other each week for a weeklong series, and often used Monday as the travel day between series. In this instance, the game was played on the Monday since Sacramento only had to travel to Portland for its next series. The Indians’ next opponent was the Salt Lake City Bees, who would be coming up from Portland.